By Sam Piha

|

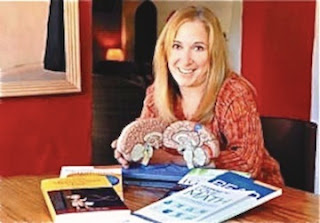

| Dr. Judy Willis |

Judy Willis is a leading thinker on how to apply new brain research to better promote children's learning. Below is part 1 of an interview with Dr. Willis. Check out her video on Edutopia, which we aired at the How Kids Learn conference.

Q: Can you briefly tell us about your background and current career in education, and why you made this change?

A: The school experience started changing about 12 years ago with over-stuffing of the curriculum – more and more wrote facts for children to memorize starting in first grade. Many more children were referred to my office by teachers who thought they might have neurological conditions.

It turned out what looked like ADHD, OCD, and staring spell “petit mal” epilepsy were not the problems. These children’s brains were going into survival mode from the stress of boredom and frustration. I investigated the potential source of this huge jump in referrals. The kids, when I evaluated them, usually didn't have any of these conditions.

The cause, as I observed was in the change in classrooms where the pressure to pack too much information into students’ brains was changing the part of the brain in which children were processing information and emotions. In the stress state, input does not reach the highest, reflective and cognitive brain (prefrontal cortex) where it needs to go to become memory. Stress diverts flow to the lower “reactive” brain where the outputs are limited to the same type of responses of other mammals when they are stressed: fight, flight, and freeze. In the classroom these same involuntary reactions to stress were the reasons students appeared to be “acting out” or “zoning out”.

I believed my background as a neurologist and neuroscientist could help me teach students so they could acquire the required material in memory, but do so with the joy and positive connections to learning that would reduce the damage they were experiencing from chronic school-related stress.

I went back to the university, earned my teaching credential and masters in education, and for 10 years taught elementary and middle school. I now teach educators and parents throughout the world, and write books about using brain research to guide parenting and teaching strategies.

Q: Is there any advice, based on your understanding of the new brain research, that you would give to out-of-school time workers?

A: The knowledge gained from brain research, when applied to learning, can energize and enliven students’ minds, improve memory, focus, organization, and goal setting. Strategies that incorporate brain-based learning research include building upon children’s natural curiosity with discovery and investigations to sustain their inherent love of learning.

The school years are critical times in a children’s development of self and relationships to the world. This is when educators need to give children opportunities to gain access to a new compendium of tools they will need to understand and participate successfully in the world. This approach to teaching enriches children’s classroom experiences, keeps alive their natural curiosity, and cultivates their enthusiasm for life-long learning.

New information is being discovered and disseminated at a phenomenal rate. It is predicted that 50% of facts children are memorizing today will no longer be fully accurate or complete in the near future. Children need to know how to evaluate sources of accurate information and then to use critical analysis to assess the veracity/bias and current/potential uses of new information.

Students need to have school experiences to prepare them to analyze information as it becomes available, adapt flexibly when what were believed to be facts are revised, and to collaborate with other experts on a global playing field. These qualities require educational experience that not only build knowledge but also tolerance, judgment, critical analysis, evaluation of source validity, risk assessment, goal-planning, ability to articulate their ideas clearly, and cognitive flexibility, including willingness to consider alternative perspectives.

To build the capacity for creativity and innovation, students need opportunities to make decisions and deal with choices and uncertainty, rather than be given the answers or told what is right. This starts when children are young and receptive to taking on challenges, but still knowing teachers are there for support, feedback, and to encourage their revisions.

With these higher cognitive opportunities to build the neural networks of cognition and reflection, curiosity is promoted. Students' brains are attentive because they learn to focus attention on and evaluate information to satisfy their curiosity. This makes school a natural progression of childhood curiosity and builds not only a positive attitude toward school, but promotes the neural construction of thinking and innovation.

With the support and experiences of top summer and after school learning, smiles can replace groans and eye-rolls. This is when the correlations of neuroscience to education return to children the joys of learning. Children’s brains will have the capacities to achieve their highest potentials as they inherit the challenges and opportunities of their 21st century.

_____________________

Dr. Judy Willis, a board-certified neurologist in Santa Barbara, California, has combined her 15 years as a practicing adult and child neurologist with her teacher education training and years of classroom experience. After five years teaching at Santa Barbara Middle School, and ten years of classroom teaching all together, this year Dr. Willis reluctantly left teaching middle school students and dedicated herself full-time to teaching educators. With an adjunct faculty position at the University of California, Santa Barbara graduate school of education, Dr. Willis travels nationally and internationally giving presentations, workshops, and consulting while continuing to write books for parents and educators.